Religion,

Secularism, and European Integration

European

Liberal Forum seminar

on “Churches and States in the Civic Identity

Process”, June 26th 2008,

premises of the Representation of the European Commission in Barcelona.

Opening

conference speech by Giulio Ercolessi (Audio).

There

was a sort of foreword to this seminar in Barcelona. This is

indeed the

last one in a series of seminars. The first one was a fringe session

held in

Bucharest, in connection with the ELDR conference there, in October

2006, when

we were still an informal network of liberal think tanks. The Bucharest

meeting

was introduced by Professor Ingemund Hägg and I. It was there

that we realised

that, although very widely shared, some of the ideas and principles

stated in

the paper we had drafted appeared to be debatable also in the eyes of

some of

us.

The title of

the paper was “A liberal contribution to a

common European civic

identity”. It seemed to us that secular and religiously

neutral public

institutions were one of the most typical liberal contributions in

shaping our

European civic identity (at least the sort of paradigmatic originally

Western

European political identity we usually think of when we say

“European”).

Actually, I

think most of us usually underestimate how much and how

deeply

European liberalism, i.e. our own political and cultural family, has

shaped, in

the end, the face of our civilisation, of contemporary Europe, indeed

of the

Western World, and, hopefully, of a great part of the world. Of course

we

should also never forget that was just the final outcome, after

successfully

overcoming many “challenge and response” historical

situations (according to

Arnold Toynbee’s model): and we have to remember that the

possibility of

failure is always there, if we are not able, or not willing, to respond

to the

new challenges of our time. We also usually underestimate how much we

are seen

by others as a part of the world with a common, very peculiar and

recognizable,

cultural, civic and even political identity. This is not so obvious at

all for

many of our fellow Europeans, nor is it so obvious that there are new

challenges to which we are called to give new responses.

Two other

assumptions in our Bucharest paper proved not to be so

obvious to

everybody: that we have – and need – a common

European identity and that this

cultural European identity can only be a civic one.

All these three

assumptions – we need secular institutions,

we need to be aware

of our common European identity, we need it to be a civic one

– have to be

argued for.

Our European

Liberal Forum is a suitable instruments to tackle issues

of this

kind, given that political parties appear to be no longer the proper

instrument

for long-term political and strategic discussions. Indeed, the process

that is

forcefully turning professional politics into showbiz is also enticing

politicians

into becoming more and more followers rather than leaders, many of them

paradoxically feeling forced into being full-time engaged in miming a

natural

charisma, that is more and more required, by electioneering techniques,

at

almost any level of political representation nowadays, and that most of

them

inevitably lack.

National

political and cultural histories can very largely interfere

with the

perception of these issues, and all the three assumptions mentioned

above have

much to do with them. We cannot even think of imposing any common view,

but it

is time to face and discuss these problems at least at EU level.

First point: of

what kind of identity are we talking about?

There are

analogies between individual identities and public ones,

i.e., they

are always built in connection (not necessarily in competition, or,

worse,

against, even if the latter has unfortunately usually been the case in

history), with others; they help, and are indeed necessary, to be able

to say

“I” or “we”: they imply a

difference with the world outside.

This is a first

obvious obstacle for us: even if we realistically know

and do

not expect that our liberal principles are universally shared, we have

always

attached to our values a universal vocation and often successfully

managed to

have them declared universal – often with some reluctant

assent by others.

Anyway, we will always be more than reluctant to accept that our

political

values remain for ever a continental (or little more than a

bi-continental)

peculiarity.

In any case,

the common identity we are talking about here is a

political one.

It has to do with the “sense of historical

individuality”. That was the

definition of the idea of nation, in the solely European, non global

world,

that exists no more, that was given by historian Federico Chabod, an

antifascist intellectual who long investigated

the roots and nature of the idea of nation and of the idea of Europe:

not by

chance, he was born in Valle d’Aosta (Vallée

d’Aoste), an Italian frontier region

that was disputed immediately after World War II between Italy and

France.

Individuals in

free societies must be free to adopt multiple identities

of

their own choice, and not be bound to the ascribed components of their

personal

identity, set once for ever by luck when they were born. And also

national

identities have always been multi-folded and matter for interpretation:

think

of Dickens’s (and Disraeli’s) “Two

Nations”, of “les deux Frances” in

French

historiography; Britain can be thought of as the cradle of individual

freedom

and parliamentary democracy, as well as the antonomastic imperial and

colonial

power; much the same could be applied to the US in the XX century.

When liberal

and democratic customs and institutions were first

established in

a few European nations, they represented the peculiar identity of those

very

nations (early Dutch tolerance, the British Bill of Rights, the US

Declaration

of Independence and Constitution, French “Principles of

‘89”).

At least since

the end of World War II these principles are no longer

typical

of a small number of individual nation-states, and have rather more and

more

grown as the core of the common political identity of the Western

world. (And

in Western Europe – and now also in Central Europe after the

fall of communist

rule – it has probably been the violence – rather

than any supposed original

irenic cultural vocation – of our past history that prompted

us today to share

a keener sensitivity for issues such as the stiffness of the criminal

justice

system, the death penalty, police brutality, guns control and universal

protection from life’s harshness, than many Americans

probably do).

These

principles are nowadays so widely shared among Europeans that we

often

consider them as already consolidated as universal. We are therefore

even led

no longer to consider them as typical of our civilisation.

Globalisation should

awake us from that illusion. Political bodies in liberal democracies

should

stand for the liberal democratic principles of their constitutions and

charters: if we did, we would also be much more aware that we are

talking of

that part of our identity that allows us to say

“we”.

Hopefully,

these basic democratic principles are, or at least should

be, shared

by the vast majority of our people – even if many have no

idea of how liberal

these principles are. That does obviously not exclude that there will

always be

extremist lunatic fringe groups that do not share these basic

principles: we

have no totalitarian vocation, we respect also radical dissent, but we

should

not be neutral. Especially in the multicultural societies we live in,

we should

stand for our liberal principles and argue for them in all political

and social

arenas, as well as in our educational systems.

The second

issue: do we need a European identity?

This could

obviously be the matter for another entire series of

seminars. And

we actually started tackling the issue, from its geopolitical side, in

the

Helsinki seminar on multilateralism we held two weeks ago.

Here I would

just stress that, at this point of our history, it is a

simple

matter of survival. GNP is obviously not the only unity of measurement

of the

international weight of countries or civilisations, but it is

meaningful enough

just to take a hint[i].

Politicians may

have to respond to day-to-day urgencies, but it is

inescapable

to face these problems. We have to remember that:

a) in a

democracy the rights of the people are paramount, but the

duties of

political and cultural élites are not less vital for a

democracy to survive (as

an Italian citizen, I unfortunately know what I am talking about);

b) in almost no

European country the nation-building process and the

building

of a national identity has been a “natural” or

“spontaneous” process.

Individual

European states today cannot cope with globalisation. In

order to

survive in the global world and in order to assert our interests,

values and

principles, Europe must have a say. In order to have a say Europe must

have an

international policy. In order to have an international policy it must

have a

European political system capable of effectively deciding one. Common

policies

require common politics and common institutions. We are in the middle

of a

crisis of European integration, everything is obviously even more

difficult

after the French, Dutch and now Irish referenda, but the alternative is

acting

as Snow White and the Twenty-seven (not just seven) Dwarves. Just think

of what

the consequences would be if the Italian foreign policy had to be

decided, step

by step and unanimously, by the twenty Italian regional governments, or

if the

German foreign policy had to be set, in the same paralyzing way, by the

sixteen

Länder governments.

By the way, a

European pillar of the Western world, if one is to

survive, is

also necessary to the US, as, among others, the pitiful Iraqi story

tells.

Third point:

any European common identity must an can only be a civic

one.

The above

mentioned historian Federico Chabod outlined a scheme of the

main

ideas of nation that arose in modern Europe. He described a mainly

German

naturalistic and romantic idea dating back to Johann Gottfried Herder:

the

nation as a large family based upon blood descent and upon the

relationship

between land and stock; and a rival cultural and voluntaristic idea,

that he

saw typical of the French and Italian tradition, embodied by Ernest Renan and Pasquale Stanislao Mancini: the nation as

an everyday

plebiscite, based upon the will to share a common destiny and a common

culture.

The first notion is of no use today, after the ultimate tragedies we

faced when

the myth of ethnical uniformity ended in the Shoa and in ethnic

cleansing. But

the second too is outdated in the pluralistic societies we live in.

Much more

useful to us is Jürgen

Habermas’s idea of “constitutional

patriotism”. This

idea was born when Germany was still divided. Habermas thought that

Western

Germans should consider their 1949 Grundgesetz, their

post-war liberal, democratic and federal

constitution, rather than any of the previous ideas of

“little” or “greater”

Germany, as the core of their political identity.

This is far

from being an artificial intellectual construction: as Maurizio Viroli, a Princeton

Italian

historian, has recently shown in a philological research, the very idea

of love

for one’s “patria, patrie” was

originally meant as the love for the liberty typical of that

nation’s institutions.

If not a

patriotism of the, unfortunately not yet existing, European

constitution, we should in essence build up a patriotism of the

European

Grundnorm: forcing somehow Hans Kelsen’s

idea of the Grundnorm (the basic norm of a

constitutional system), that is the ultimate political decision on

which every

constitution is grounded and built upon. In order to do this, we should

make

our fellow citizens much more aware of the relevance and peculiarity of

the

system of liberal democracy, rule of law and human rights that is today

a

common heritage of our countries.

In our

pluralistic societies, enriched by the most diverse individual

cultural

and life-style choices, and where integration of foreigners and former

immigrants and their offspring in the rules of liberal democracy is

paramount,

is there any other road to integration? Of course, ethnic

identification, or

the establishment of a narrowly national perimeter inside which

traditional

customs become almost compulsory for everybody, are of no use today:

not at the

European level only, but also inside each of the old individual

European

nation-states.

Inside such a

political and ideal civic framework many – not

all of course –

misunderstandings could perhaps be avoided. Think for example of the

German

controversy on the idea of a national Leitkultur, prompted by a

German

intellectual of Syrian origin, or think of the speech made there by

Turkish

Prime Minister Erdoğan, who labelled integration as “a crime

against humanity”

(a translation mistake, it was said, he meant assimilation...).

As a conclusion

let’s come to the core of this series of

seminars discussion:

our idea of a common European, and civic, identity needs secular public

institutions.

It is not, of

course, because our societies have now grown more

religiously

pluralistic due to immigration, that liberals prefer religiously

neutral public

institutions. The fight for religious freedom is at the very roots of

European

liberalism – and European liberties. We often forget that

this fight for

religious freedom was from the start a fight against the intolerance of

established churches, and just in the end a fight against the state

atheism of

communist countries or against the surge of Islamic fundamentalism.

Indeed, non

religiously neutral public institutions are always an infringement of

the equal

social dignity of individuals.

But in

multireligious societies it is also unrealistic and fanciful to

advocate

for any sort of religious supremacy and expect integration at the same

time.

Religious

freedom is not just the freedom to practice the religion of

one’s

ancestors (the issue as such would never have been even raised in

post-Reformation Europe). It is also the individual freedom to

relinquish one’s

ancestors’ religion.

One thousand

years ago, Europe could have been described as synonymous

for

Christendom. No longer since the process that lead to the birth of the

modern

idea of individual in the late Middle Ages, in Northern and Central

Italy, in

the Flanders and in England, and to the Reformation, possibly its most

relevant

consequence, that lead in turn to the first embryo of a political

system based

on (partial) religious freedom, rule of law and representative

democracy, after

the Great Rebellion and the Glorious Revolution in XVII century England.

It is this

individual that has been for possibly more than four

centuries now

the subject of religious freedom, as of all the other liberal

liberties, as has

always been very well known by the freedom fighters belonging to

religious

minorities oppressed by established churches.

The biggest

challenge of our time is the paradoxical erosion of the

precious

civic and historical values typical of our identity by populist

politicians

that, in the name of what they call “our roots”,

“our identity”, would like to

cage all of us back into closed homogeneous and mutually hostile

communitarian

enclosures, the smaller and the more controlled the better.

And, once

again, new threats came from religious intolerance, both

autochthonous and imported. Let’s be clear: our freedom was

first established

not only by those free-thinkers and libertines who wanted to get rid of

any

religion that they deemed always superstitious, but also –

also – by those

believers who wanted to be free to worship their God in a different way.

But there is a

temptation, once again, even in some Christian churches

– and

most of all in the Vatican hierarchy – to take advantage of

the “revanche de Dieu”

that has spread

out since the Islamic revival that became manifest with the Iranian

revolution

thirty years ago: a temptation to counterbalance the Islamic surge not

by

strengthening the alternative values of open and free societies, but,

on the

contrary (where they can: the Spanish state is obviously not the case

today,

but Italy, Poland or Ireland are), by relegating non-believers in a

position of

second class citizens, by imposing on all of us, by law, benefits or

disadvantages depending on personal behaviours only consistent with a

faith

many of us do not share – and that even fewer share in its

strict traditional

interpretation, as it is the case of millions of Catholics believers;

or at

least by imposing on all of us to pay more taxes in place of those

whose faith

is not strong enough to contribute financially to the life of their own

churches; by requiring that religious faiths and religious people and

leaders

be given a privileged rank in our secularised societies. In Italy the Critica liberale foundation has

been

performing a yearly survey that now covers more than fifteen years: it

shows

that, the more the actual behaviours of the Italian population become

secularised, the more power and public resources are given by

politicians to

the Catholic hierarchy[ii].

And it is a

matter of controversial ethical issues, an area where no

liberal

society can allow religious people to have public institutions

interfere in the

lot of those who do not conform to their wishes and who do not want be

imposed

behaviours that are inconsistent with their own principles, opinions

and

beliefs in the domains of education, marriage, divorce, family law,

abortion, sexual

life, freedom of scientific research, living will, euthanasia.

But it is also

a matter of equal social dignity and freedom for every

single

individual, even those who choose, like heretics and reformers in our

history

centuries ago, to object, to reject or to relinquish the faith and the

traditions of their ancestors.

Even more, it is a matter of individual freedom and non discrimination

for

those on whom public institutions are led by some religious leaders and

by populist

politicians to impose behaviours or regulations inconsistent or

disrespectful

of their own ascribed identity (as is the case of homosexuals), or are

even

imposed by public institutions an officially ascribed identity that no

one

knows whether they accept or not (as is the case of our younger fellow

citizens

who are the offspring of immigrated families).

I can’t see how

liberal values and principles can be enforced in any

institutional or ideal framework different from our great and

successful

liberal tradition of religious neutrality and separation – as

large as

practically feasible – between religion and political power.

[i]

Percentage

of gross world product: WMF 2005

data. Goldman Sachs 2030 and 2050 projections.

|

Paesi

|

2005

|

2030

|

2050

|

|

Cina

|

4,3

|

13,5

|

19,1

|

|

India

|

1,5

|

4,6

|

12,0

|

|

Usa

|

29,4

|

19,6

|

15,1

|

|

Germania

|

5,0

|

2,5

|

1,5

|

|

Uk

|

4,2

|

2,5

|

1,6

|

|

Francia

|

3,7

|

2,1

|

1,4

|

|

Italia

|

3,1

|

1,6

|

0,9

|

|

Ue-25

|

29,5

|

18,2

|

10,6

|

Source:

Renato Ruggiero, Equilibri globali. Le economie stanno bene.

i governi un

po’ meno, Il Sole 24 Ore, February 10th 2007.

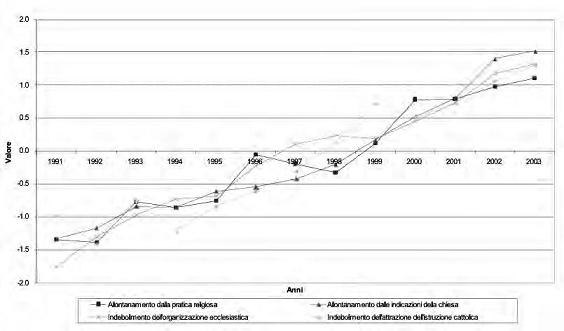

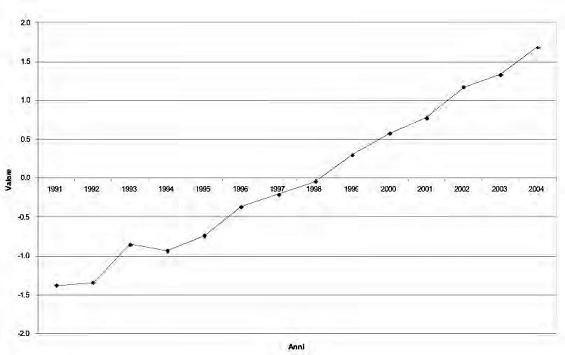

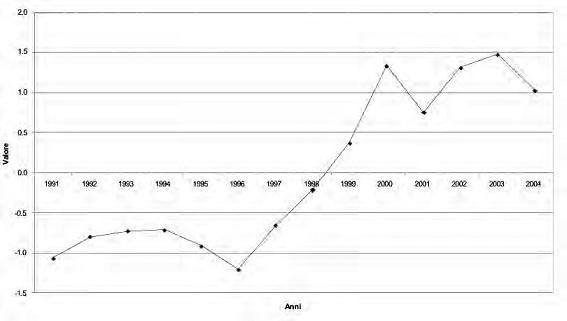

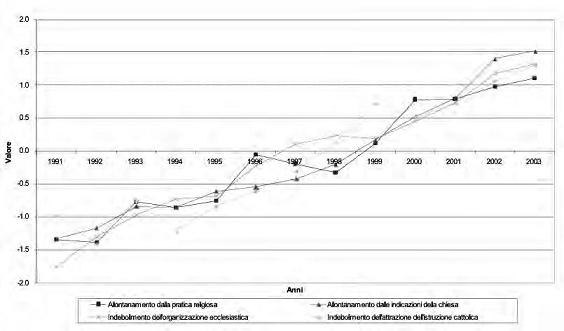

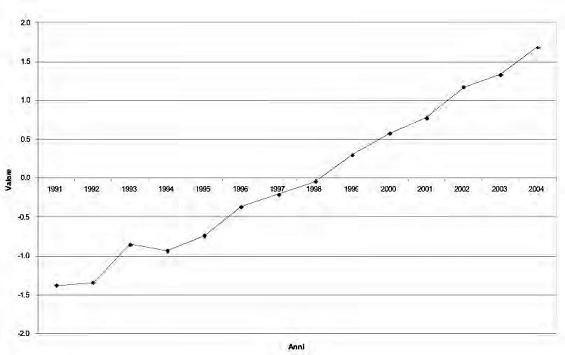

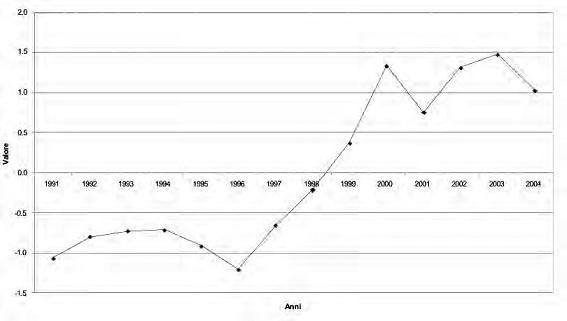

[ii]

Secularisation

macroindicators

Secularisation

Index

Institutional

presence of the Roman Catholic Church

Source:

Renato Coppi, Laura

Caramanna, L’indicatore di

secolarizzazione, Critica liberale n.135-137, Jan.-Mar. 2007.

Files released on this site by Giulio

Ercolessi are licensed under a

Creative

Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.5 Italy

License

.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://www.giulioercolessi.eu/Contatti.php.